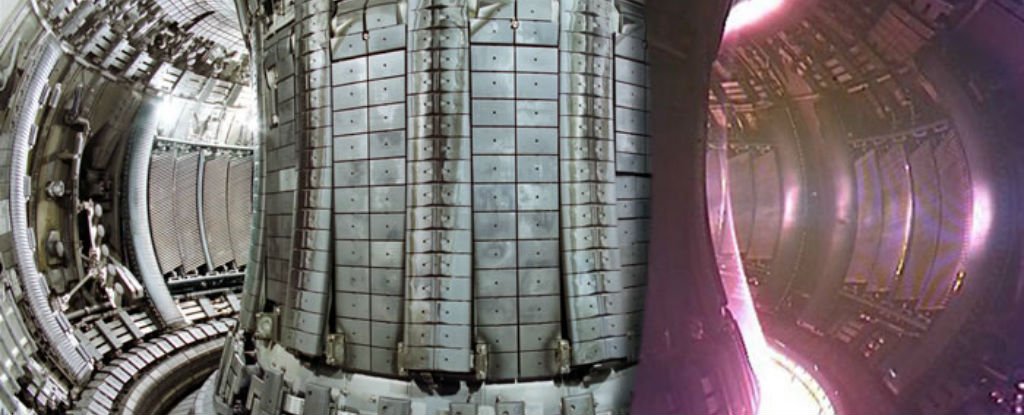

Scientists have invented a new type of metal to make nuclear reactors stronger and safer

Bring on the future.

An international team of researchers has developed a new type of metal alloythat could make nuclear reactors safer and more stable in the long term. The new material is stronger and lasts longer than steel - the metal of choice for current nuclear reactors.

Nuclear reactors typically last for 40 years, because steel can become weaker or even defective over time. So the hunt is on for something to replace it and guarantee the future of nuclear power, which is currently providing 11 percent of the world's electricity. The fact that modern-day reactors run at higher temperatures than ever before makes the search even more urgent - currently, if the steel exterior of the reactor becomes defective, it needs to be replaced, and that takes a huge amount of time and money.

High-entropy alloys, which use several elements in equal percentages, could be the solution, according to researchers from the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee and the University of Finland.

To test their hypothesis, they bombarded two such alloys with nickel and gold ions - a simulation of what happens to the metal casing inside a nuclear reactor. In each case, the alloys came out with two or three times fewer defects than steel.

As atoms are split inside a nuclear reactor, intense levels of heat are produced - to power the turbines and generate electricity - as well as more and more neutrons. Most of these neutrons get trapped by the heavy water that fills the reactor, but some make it to the metal exterior that holds everything together, and that can cause defects as they dislodge the atoms forming the metal's crystalline structure.

Because high-entropy alloys use equal mixes of metals spread out evenly, each type of atom is nearly equally exposed to the incoming particles, thus levelling out the chances of dislodging slightly different-sized atoms and reducing the risk of defects.

While high-entropy metals aren't new, it's only in recent years that scientists have managed to create them to a high enough quality to use for practical applications, and while cost remains a problem, this should start to come down in the years ahead.

As New Scientist reports, these alloys won't be ready to use for a long time yet, but full-scale tests are planned, and there are many different metal alloy mixes that scientists can try as they look to perfect the formula.

"We are very happy but I wouldn't dare yet to build a nuclear reactor out of these materials," said one of the team, Kai Nordlund from Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

The team's work is due to be published in Physical Review Letters.

Comments

Post a Comment