Scientists say they’ve found a particle made entirely of nuclear force

Enter, glueball.

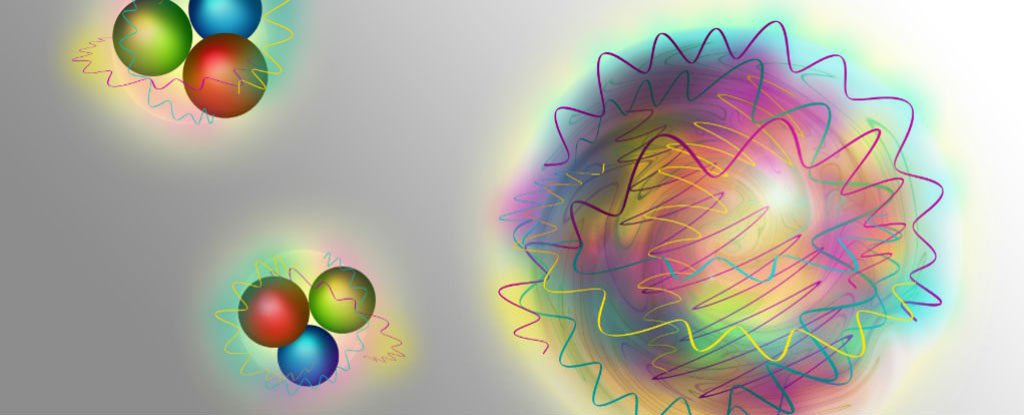

After decades of searching, scientists say they’ve finally identified a glueball - a particle made purely of strong nuclear force.

Hypothesised to exist as part of the standard model of particle physics, glueballs have eluded scientists since the 1970s because they can only be detected indirectly by measuring their process of decay. Now, a team of particle scientists in Austria say they've found evidence for the existence of glueballs by observing the decay of a particle known as f0(1710).

Protons and neutrons - the particles that make up everyday matter - are made of minuscule elementary particles called quarks, and quarks are held together by even smaller particles called gluons.

Also known as 'sticky particles', massless gluons are described as a complicated version of the photon, because just like how photons are responsible for exerting the force of electromagnetism, gluons are in charge of exerting a strong nuclear force. "In particle physics, every force is mediated by a special kind of force particle, and the force particle of the strong nuclear force is the gluon,"explains one of the researchers, Anton Rebhan from the Vienna University of Technology.

But there is one major difference between the two: while photons aren’t affected by the force they exert, gluons are. This important fact means that while photons can’t exist in what’s known as a bound state, gluons can be bound together via their own strong nuclear force to form glueballs.

"The existence of glueball particles brings the idea that, not only can particles be forces or force carriers (i.e., photons), but that these massless particles are also contingent upon the force that they are made up of, allowing glueballs to exist in a static state," J.E. Reich writes for TechTimes.

Gluons might be massless on their own, but their interactions with each other give glueballs a mass, which, theoretically, allows scientists to detect them, if only indirectly through their decay process. And while several particles have been identified in particle accelerator experiments as being viable candidates for glueballs, until now, no one’s been able to make a convincing case for any of them consisting of pure atomic force.

The closest scientists have gotten to finding a glueball is narrowing in on two possible candidates: f0(1500) and f0(1710), which are subatomic particles calledmesons that are usually composed of one quark and one antiquark each. For a while, f0(1500) was considered the more promising candidate of the two, because while f0(1710) produced better results when applied to computer models, its decay process produced heavy quarks - also known as 'strange quarks'.

This was a problem, because some scientists assumed that gluon interactions did not usually differentiate between heavier and lighter quarks - something that Rebhan and his colleagues say they’ve reconciled in their calculations, published in Physical Review Letters today. "Our calculations show that it is indeed possible for glueballs to decay predominantly into strange quarks," he says, explaining that when the decay pattern for lighter quarks was also measured for f0(1710), the results agreed "extremely well" with their model.

The researchers are hoping the new data from experiments at the Large Hadron Collider at CERN (TOTEM and LHCb) in Switzerland and an accelerator experiment in Beijing (BESIII) will help them strengthen their case for f0(1710) being a glueball. "These results will be crucial for our theory," says Rebhan. "For these multi-particle processes, our theory predicts decay rates which are quite different from the predictions of other, simpler models. If the measurements agree with our calculations, this will be a remarkable success for our approach."

Need a crash course in quarks, strange quarks, and all the rest? Physics Girl has got you covered:

Comments

Post a Comment